Comment:

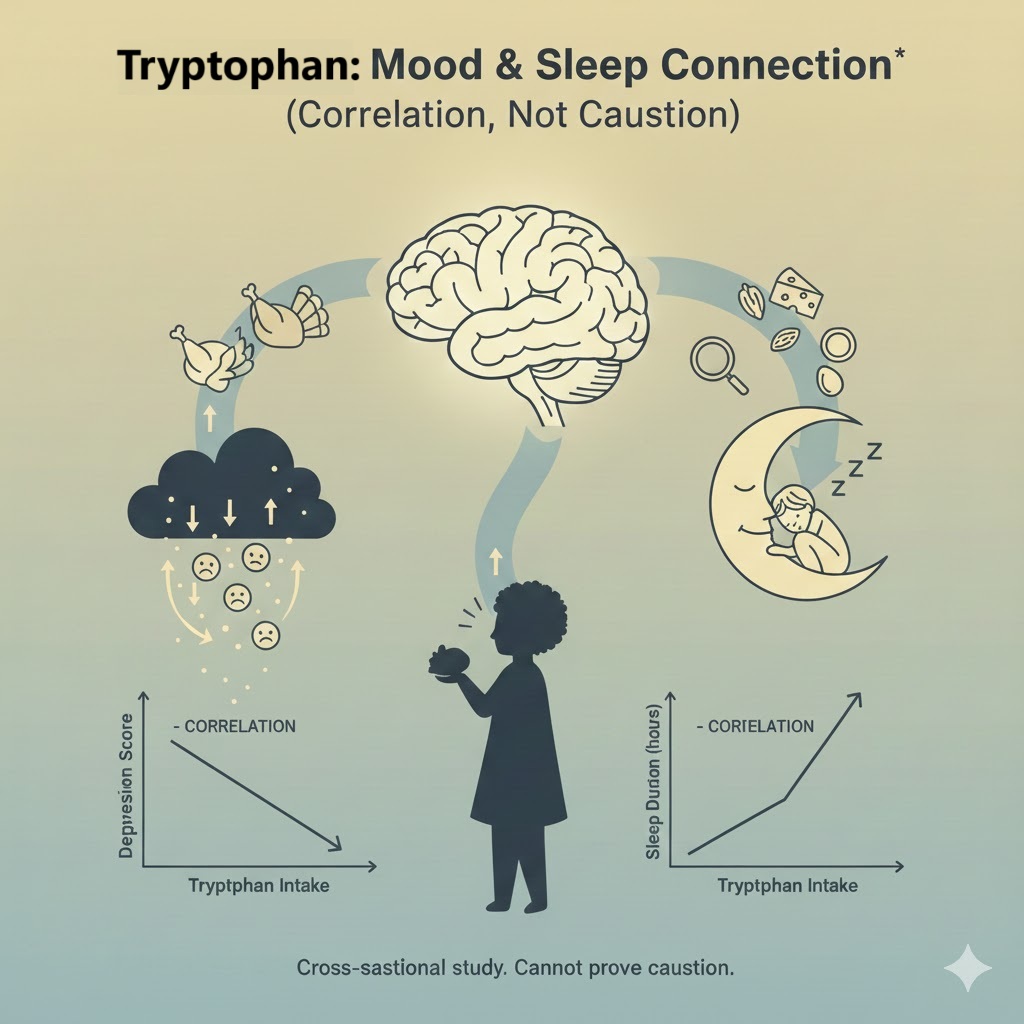

It’s Thanksgiving, and I figured it would be fun to see if there was any actual research on turkey and sleepiness. There isn’t, but I came across this interesting study showing that tryptophan is associated with both improved sleep and decreased depression symptoms.

Despite it’s reputation, turkey is actually about equivalent in tryptophan to chicken, and lower than tofu per serving.

🥩 Tryptophan Content per Typical Serving

| Food | Tryptophan (mg) per Serving | Typical Serving Size |

Tryptophan (mg) per 100 g

|

| Tofu (firm, raw) | 407 | 140 g (approx. 1/2 block) | 291 |

| Chicken Breast (cooked, skinless) | 261 | 85 g (approx. 3 oz serving) | 307 |

| Turkey Breast (cooked, skinless) | 258 | 85 g (approx. 3 oz serving) | 303 |

| Pork Tenderloin (cooked) | 239 | 85 g (approx. 3 oz serving) | 281 |

| Salmon (cooked) | 170 | 85 g (approx. 3 oz serving) | 200 |

| Sesame Seeds | 113 | 30 g (approx. 1/4 cup) | 378 |

| Parmesan Cheese | 110 | 30 g (approx. 1 oz) | 365 |

| Milk (2%) | 101 | 240 mL (approx. 1 cup) | 42 |

| Sunflower Seeds | 93 | 30 g (approx. 1/4 cup) | 310 |

| Oats (dry) | 93 | 40 g (approx. 1/2 cup) | 233 |

| Cheddar Cheese | 82 | 30 g (approx. 1 oz) | 274 |

| Almonds | 61 | 30 g (approx. 1/4 cup) | 202 |

| Eggs (large, whole) | 61 | 100 g (approx. 2 eggs) | 123 |

Summary:

Clinical Bottom Line

This large cross-sectional study of US adults suggests that higher dietary tryptophan intake is inversely associated with self-reported depression and positively associated with sleep duration. Importantly, the study provides evidence that the typical tryptophan intake levels in the US population (mean intake of 826 mg/d) are well above the Estimated Average Requirement (EAR) and appear to be safe, with biochemical markers for liver and kidney function remaining within normal ranges.

Clinicians should note that while this finding is biologically plausible (tryptophan is a precursor to serotonin and melatonin, which affect mood and sleep), the cross-sectional design prohibits concluding a cause-and-effect relationship. Higher tryptophan intake may simply be a marker for an overall healthier diet or lifestyle.

Results in Context

Main Results

-

Tryptophan Intake: The mean usual tryptophan intake in US adults was 826 mg/d (∼40% higher in men than women), which is several-fold higher than the Estimated Average Requirement (EAR) of ∼280 mg/d for a 70 kg adult.

-

Depression: Usual tryptophan intake was inversely associated with self-reported depression symptoms. This association remained statistically significant after adjusting for total protein intake for the overall population and for women specifically. An inverse association means higher tryptophan intake was associated with lower depression scores. The severity of depression was measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) raw score (0-27) and calculated level (1=no depression, 5=severe depression).

-

Sleep Duration: Tryptophan intake was positively associated with self-reported sleep duration in the total population after adjusting for protein intake (P-trend = 0.02). A positive association means higher tryptophan intake was associated with longer sleep duration.

-

Safety Outcomes (Liver/Kidney Function): Tryptophan intake was not related to most biochemical markers of liver function (e.g., AST, GGT, LDH), kidney function (e.g., BUN), or carbohydrate metabolism (glucose, insulin) after adjusting for total protein intake. All measured biochemical markers were well within normal ranges, even at the 99th percentile of intake, suggesting that typical US intake levels are safe.

Definitions

-

Inverse Association: A relationship between two variables where they move in opposite directions. In this case, as tryptophan intake increased, the PHQ-9 depression score decreased.

-

Positive Association: A relationship where both variables move in the same direction. Here, as tryptophan intake increased, sleep duration increased.

-

Estimated Average Requirement (EAR): The daily intake value that is estimated to meet the requirements of half the healthy individuals in a life stage and gender group.

Assertive Critical Appraisal

Limitations & Bias (STROBE Framework)

-

Cannot Determine Causation: The cross-sectional nature of the NHANES survey is a major limitation, as it only assesses exposure (tryptophan intake) and outcomes (depression, sleep) at a single point in time. Therefore, the study cannot establish that higher tryptophan intake causes lower depression or longer sleep. The association could be due to reverse causation (e.g., people who are less depressed might eat healthier, protein-rich diets) or confounding.

-

Self-Reported Measures: The data rely on self-reported measures for food intake (24-h recall interviews), depression (PHQ-9 questionnaire), and sleep duration. Self-reported data can introduce recall bias and social desirability bias, potentially affecting the accuracy of the associations.

-

Incomplete Tryptophan Data: The authors noted they did not have tryptophan content for approximately 10% of the total protein consumed, which could lead to some misclassification of true tryptophan intake.

-

Residual Confounding: While the authors attempted to address confounding by adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, physical activity, smoking, alcohol use, and critically, total protein intake, there is still potential for unmeasured confounding (e.g., overall diet quality, socioeconomic status, other lifestyle factors) to influence the results.

Reporting Quality Assessment (STROBE)

The reporting quality is high for an observational study using a national database. The authors clearly described their efforts to address confounding by using a comprehensive set of covariates in their adjusted models, including protein intake to isolate the specific effect of tryptophan. They explicitly stated the limitations of the cross-sectional design and the use of self-reported data.

Applicability

The findings are highly applicable to a general clinical practice in the US, as the study uses a large, nationally representative sample of US adults. It provides reassurance on the safety of typical dietary tryptophan intake and suggests that promoting tryptophan-rich foods may be part of a broader strategy for mood and sleep, but definitive dietary recommendations for these outcomes cannot be made from this study alone.

Research Objective

The objective was to examine the intake of tryptophan and its associations with biochemical markers of health- and safety-related outcomes, self-reported depression, and sleep-related variables in adults, using a secondary analysis of the NHANES database.

Study Design

-

Study Design: Cross-sectional analysis of aggregated data from multiple cycles of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

-

Data Used: NHANES data from 2001-2012.

-

Tryptophan Intake Measurement: Estimated from reliable 24-hour dietary recalls using the USDA’s automated multiple-pass method, with amino acid data obtained from the USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference.

-

Outcome Measurement:

-

Biochemical Markers: Nonfasting blood specimens were used for liver function (ALP, ALT, AST, GGT, bilirubin) and kidney function (BUN, creatinine, GFR).

-

Depression: Assessed using the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) via a computer-assisted personal interview.

-

Sleep: Assessed by a single question on self-reported sleep duration (hours).

-

Setting and Participants

-

Setting: Nationally representative sample of noninstitutionalized US adults.

-

Participants: 29,687 adults (15,031 men and 14,656 women) aged ≥ 19 years.

-

Exclusions: Pregnant and/or lactating women and individuals with incomplete or unreliable 24-hour recall data.

Bibliographic Data

-

Title: Tryptophan Intake in the US Adult Population Is Not Related to Liver or Kidney Function but Is Associated with Depression and Sleep Outcomes

-

Authors: Harris R Lieberman, Sanjiv Agarwal, and Victor L Fulgoni III

-

Journal: The Journal of Nutrition

-

Year: 2016

-

DOI: 10.3945/jn.115.226969

Original Article:

Full text: here